“Ecology is the science of understanding of consequences” - Frank Herbert, Ecologist, 1969.

The above quote, taken from an interview from the ecologist and author of the hit Sci-Fi book series Dune, succinctly captures everything that ecology stands for. That in nature, nothing exists alone, everything is interconnected in a causal web, and anything can looked at as an effect of something else that is happening nearby. An ecosystem, therefore, is when when each link in this delicate, metaphorical web works with others to make the web stronger as a whole. On the desert planet of Arrakis, this looks like desert mice opening up the arid dirt to make way for plants, birds of prey keeping watch to keep the mice under control, insects reaching niches that the others can’t, and the desert bat to keep even those bugs in check. Just one of these links getting out of control, like mice multiplying too quickly because the resident birds got displaced in a sandstorm, can cause the whole system of order to collapse and all participants, all life, that depended on it to vanish with it. The grass needs the grasshopper and the owl, need each other.

If all life in an ecosystem depends on maintaining that balance, and we also count as life and this planet counts as an ecosystem, why then, did we invent factories?

Even the idea of a factory, everything it stands for, is so unnatural. In place of an interconnected web of cause and effect, we have the assembly line, where A affects only B, which in turn affects only C and so on. Where we had restraint and balance, we now disregard the state of things around us for the sake of output yield. Even when we farm, which is not typically looked at as a “factory” but is still subject to industrial logic, biodiversity in crop selection is substituted for corn and soybean monoculture. These changes don’t come without penalty either, every time nature’s rule is violated (planting only corn in a field) nature must exact its revenge (soil degradation). All of this waste in the endless pursuit of just one more bushel of corn. I need not peel away many layers of facades to demonstrate how the factory is the antithesis to the pre-human thesis that is nature.

Now I’m beating around the bush: why did we do it? Why did we look at the beauty and resilience of nature and decide that we didn’t want the earth to continue on living for much longer? I’d gander it’s because of the very human idea that merely surviving is not really living.

Every second of every day of the life of the fly buzzing around the room while you read this is focused purely on trying to survive and reproduce. Similarly, for most humans before the advent of agriculture life was pretty focused on those two things as well. When you yourself have to catch/harvest your own food, make your own shelter, clothes, tools, warmth; there’s not a lot of time left over for other things. Generally, the more unspecialized and self-reliant you are, the more time you spend surviving. For that reason, agriculture shifted food production to just a portion of the human population, and left the rest to find other niches that were useful. It was our first of many attempts to defy nature, and do more than just work with the system. Alleviating majority of people from food duty had its perks too, they had time to do arts, sciences and invent new tools that made everything easier and more productive. Our defiance was rewarded with a surplus of time and resources, which we seem to have made good use of.

Industrialization is a continuation of our valiant fight to be lazy. Like agriculture once did for food production, industrialization shifted the production of commodities to a small subset of the population. I don’t have to sew my own clothes or figure out how to put together pieces of metal to make a car (although I have tried), there’s a factory that does it for me. I can spend my time doing other so called valuable things for society, which is cool. The sins of overconsumption and overproduction have scarred the planet and also made us fabulously wealthy.

From what I’ve seen, there are two proposed solutions to this ecological-industrial conflict that are popular in media, They are what I like to call the “Necessary Evil” and the “To Infinity and Beyond” approaches.

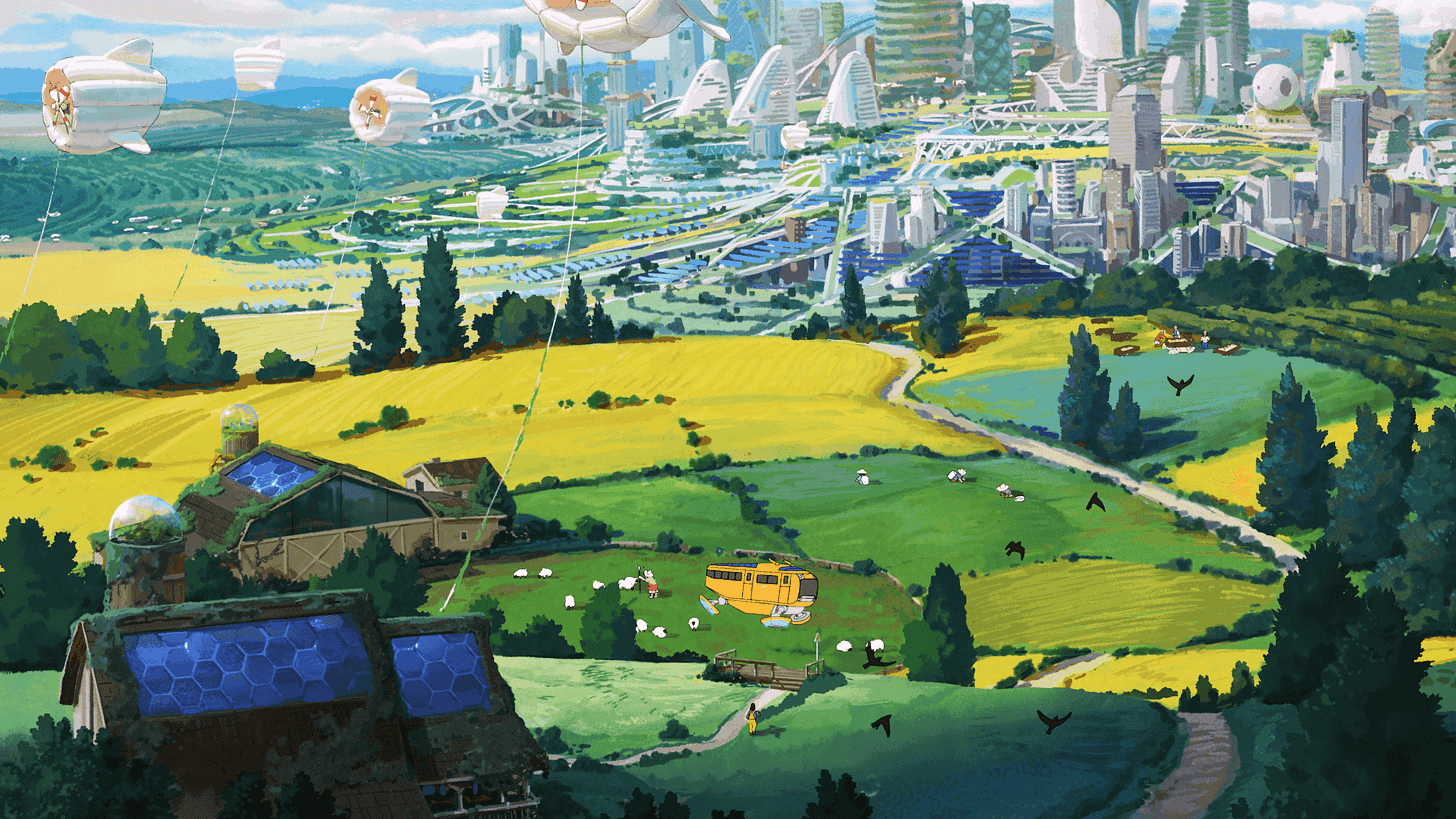

If you’ve ever been enchanted a painting such as the one above, where a tranquil and utopian society is perpetuated by solely renewable power, then you might very well subscribe to the Necessary Evil solution to industry. It goes something like this: Industrialization is killing the planet so we must get rid of the factory, reduce our consumption, and use the gifts of industry (science, tech) to once again live in an ecologically-sound system. In this light, industry is a kind of sin that has given us many good things and useful tools, but it’s not a place to stay. We can use the natural gas powered factories to create solar cells, and live off the sun just like the plants do. Everything biodegradable, nothing is wasted, we live within our means AND comfortably. That last part is crucial because if technology can’t help us stay “in the system” and lead lives of reasonable comfort/security, then we should have just stayed as hunter-gatherers. In this way, the immense amount of irreversible damage we have done to the planet by simply commuting to work 30 minutes everyday in a car isn’t in vain; we are still the good guys.

On the other hand, most science fiction space operas have a very different picture of the future. An ever-growing, space-faring race is the idea that constant expansion is a way to combat the ills of an industrialized society. You don’t have to worry about consumption if there is an essentially limitless amount of resources/planets just waiting to be harvested. The point of life is the create surplus to advance ourselves and our technology, in other words, to strive for infinity. To me at least, there’s the sense of a progression of history, and in the modern world, this ethic is most acutely represented by SpaceX.

Frankly, both of these solutions suck. They aren’t very convincing if you aren’t already the type of person who is given to the differing worldviews/attitudes that they represent.

They aren’t real solutions, they don’t hold water because neither of them are a synthesis of the ideas and desires that have produced both of these worldviews. Solarpunk is a subjugation of industry and the very important problems it solved in favor of ecology and the longevity that it represents; vice versa for the proto-typical space opera. Neither are full solutions, they are just saying “yeah I know there are problems but trust me it’s the least bad option.” Furthermore, I believe that full heartedly subscribing to one of these ideas of the future is to disregard the complete picture of humanity and our responsibility to make every life, in least in some way, worth living.

No matter how many people dream of achieving AGI or colonizing Mars, there will always be those who desire more than anything to leave to their children a better life than the one they had. There will always be naturalists and mountain men, worried parents and climate activists who enjoy nature, its gifts, and the comforting fact that this earth has persisted and will persist much longer than the short time that we spend on it. Is it reasonable to expect all of humanity to team up to raze this earth and the next ones in the pursuit of infinity? No, I don’t think so. We’d somehow have to get rid of all the people who exemplify the basic human impulse to preserve. Maybe possible but not probable, and I’m sure we can all agree, probably not a good idea.

Likewise, how can we expect everyone to stay happy and content in sustainable paradise, never producing or consuming more or less than the ecosystem allows for, when the stars stand beckoning like lighthouses on a foggy shore every night. Humans always need more, even when they don’t. It’s not reasonable that we make it this far and then suddenly give up our noble quest to conquer ourselves, the stars and everything in between.

So a real synthesis of ideas would allow us to create surplus so that we can feed our expansionist and novelty-seeking tendencies, while also not creating waste that damages the fragile and intimately connected set of things that keeps us alive. A tall order indeed. Anything less than a complete synthesis will always seem like less than a solution. In fact, the only way to adhere to one of the two options completely would be to remove diversity of temperament and opinion found in humans, by applying industrial logic to ourselves. Unfortunately, we already have a name for that method; it’s called Dystopia.

Potential solutions coming soon in Part II.